Words by Peter O’Reilly – Published in The Sunday Times, July 27th 2025

Kevin Quinn, Tennis Ireland’s CEO, is on a mission to bring through more elite junior players in a sport that is now booming at recreational level.

Ask most tennis players about their national federation and they’ll roll their eyes and say, ‘Oh God’. My experience with Tennis Ireland wasn’t greatly different. They weren’t there for me when I was growing up, so I didn’t get detailed technical coaching or play a European-wide tournament schedule. They weren’t there for me when I was going pro, either … It was just my parents and me, figuring it out as we went along. Conor Niland, The Racket

Anyone for padel? Everyone for padel, apparently. If you have a plot of 20m x 10m and a keen commercial sense, then you’re probably building a padel court for rental purposes. You’ll clean up. Such is the sport’s popularity, you’d be forgiven for wondering if tennis in Ireland is under existential threat.

Not remotely, according to Tennis Ireland’s CEO, Kevin Quinn. “There’s huge momentum for tennis here,” says Quinn, who fell in love with the sport as a junior member of St Mary’s LTC in Donnybrook. “We’ve 94,000 affiliated members but according to independent research anywhere between 150-200,000 are actually playing. We’ve a bottleneck given the demand and clubs are full. As a participation sport, tennis dwarfs rugby, for example.”

If there is momentum for tennis, though, it’s a quiet, invisible momentum, for one simple and obvious reason: this is one of the few international sports where Ireland punches below its weight. Irish tennis has never produced a star to call its own.

The Racket explains why this is so, in sobering and compelling detail. Niland reveals the caste system in professional tennis, the enormous toil and expense involved in trying to break into an elite class so self contained and precious that it makes pro golf seem a free-for-all by comparison.

Tennis Ireland doesn’t emerge positively from Niland’s account. It comes across as an amateur organisation, riven by petty and provincial politics, under-funded and short on ambition. Who would be CEO, then? Only a supreme optimist? “I could see a huge sport hiding in plain sight,” says Quinn, 54, who came with no political baggage, only an impressive record in sports administration and commercialisation. His previous gig was as Leinster Rugby’s head of commercial and marketing.

“I could see an organisation that had gone through turmoil which held the sport back, but I could also sensesome real appetite and energy for change in our clubs, which now number 190-odd,” he says. “It felt like Irish tennis was at an inflection point. “I wanted to bring some structure and process, to commercialise the sport better but also to provide a pathway, to be able to spot some talent in the huge playing community and help to bring it through. There’s no doubt in mind that Irish kids could compete at the top of this game. They just need the opportunity.”

Our conversation took place in the polite confines of Carrickmines Croquet and Lawn Tennis Club, the venue for this week’s Irish Open — a huge week for Irish tennis as the sole ITF tour event of the year and an opportunity for Irish players to win money and ranking points, but a speck in the tennis firmament.

The Irish Open is known in the trade as a “15K”, because that’s the extent of the prize-money available in the men’s and women’s competitions: $15,000 per comp, with the two winners pocketing €2,000 each — compare £3.3 million each for Wimbledon champions, Iga Swiatek and Jannik Sinner. The men’s top seed is England’s Alastair Gray, ranked 374 in the world. The top Irishman is fourth-seeded Michael Agwi, ranked 613.

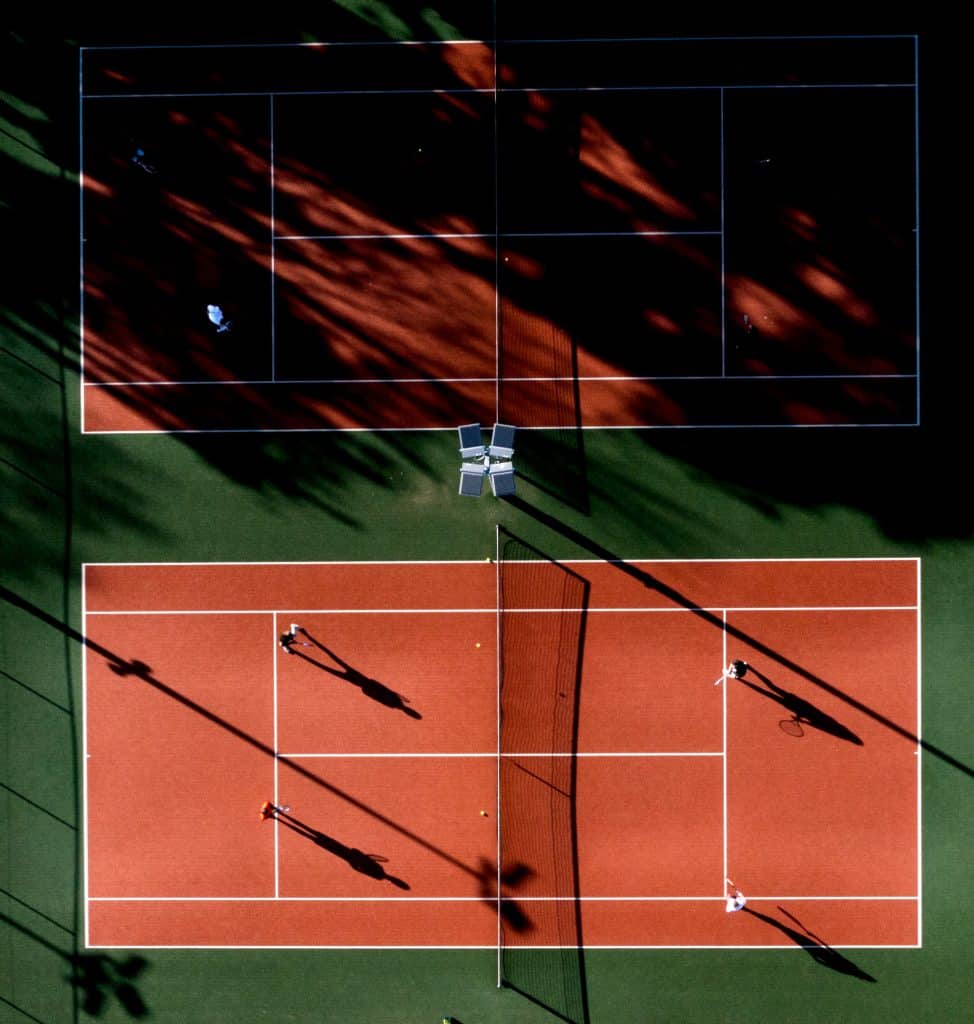

One of the advantages for the Irish competitors is that the Open will be played on artificial grass, easily the most common surface here. And yet this in itself is instructive. Clay courts are best for technical development but not best for the Irish climate and especially Irish facilities — there is not a single indoor court in Munster, for example.

Quinn’s to-do list is not so much a list as a never-ending process of upgrading and resourcing with a tiny budget of around €4 million and a staff of 35. Happily, he is relentlessly energetic and enthusiastic, especially in Open week, when there’s an opportunity to award wild cards to talented Irish youngsters. And there is talent here, he says — of the current teenage crop, he namechecks Eoghan Jennings, Zac Naughton and 15-year-old Paddy Breen, who is ranked in the world top 20 for his age grade. Quinn was irked by the assertion made in these pages recently that talent-wise, “the well is drier than ever”.

“That’s horseshit,” he says. “Ireland has never had more ranked juniors — over 100 internationally ranked juniors. This is based on there being a bigger pool of ranked players but it’s also because in the last two years we’ve focused massively on having significantly more junior tournaments in Ireland — seven ITF junior comps annually [up from three a couple of years ago] and 17 junior ranking events in total. It’s a big step in the right direction.”

Apart from his energy, surely what made Quinn attractive to Tennis Ireland was that he came from a sport — and a club — that has developed a high performance culture from humble beginnings. For Tennis Ireland, creating a performance development programme for 20 kids — ten boys, ten girls — is one step along a process that will take a generation to complete.

It will also take money. Quinn’s experience at the commercial end of rugby should be valuable. The tennis demographic is just as attractive to potential sponsors, if not more so. He mentions a “funding drive” though without specifying targets, probably because in elite tennis, there is no such thing as enough.

The cost of developing a player capable of playing at even a junior grand slam event is estimated at €100-150K per annum when you take in travel, accommodation, coaches and so on. A high-ranking British teenager can receive something like £70K support from the LTA, which in return receives around £50m annually from Wimbledon. Players — and parents — are evidently willing to make sacrifices.

Three years ago, Tracy Brennan relocated to Spain with her three talented teenage daughters simply so that Erica, Lydia and Isolde could all have ready access to top-quality coaching and ranking events, while continuing their education online. Quinn accepts that youngsters will continue to develop their tennis outside Ireland until the proper infrastructure is developed here.

“In the past, we probably said to players: You’re either with us or against us, part of our programme or not. That can’t work,” he says. “We’re building a database of all the performance players in the country, we’re looking to build relationships with tennis programmes in the US colleges, where the facilities are outstanding. We’ve also signed a memo of understanding with the LTA, which will enable our players to avail of their facilities and to play tournaments in the UK.

“We can’t fund players. Our resources are stretched as it is. But we need to work better with those private academies, with those players, those families, to help however we can.”

Small steps, but steps in the right direction.